Q4 2025 Market Commentary – Holding Steady

Q4 2025 Market Commentary – Holding Steady

Executive Summary

The U.S. economy and markets have continued to perform in 2025. Despite policy uncertainty, high valuations, and an uneven consumer backdrop, the four key legs (i.e., stimulus, the labor market, the consumer, and artificial intelligence [AI]) of the current expansion remain intact. Each shows cracks, but together they continue to support growth and asset prices.

Key Takeaways

- Stimulus remains a powerful force. Fiscal stimulus has already provided meaningful offsets to the drag from tariffs, with more than $100 billion directed toward R&D and investment this year. Importantly, much is still to be felt over the next few years. Meanwhile, the Fed has begun cutting rates after a long pause, with markets anticipating further easing into 2026. Monetary and fiscal forces are working together, prolonging the cycle.

- Labor market resilience with late-cycle cracks. Unemployment remains historically low, and layoffs are muted, but hiring has slowed and participation rates have slipped. Immigration shifts are reshaping workforce supply, especially in lower-wage industries. Stability remains for now, but this is the leg we watch most closely given its impact on consumer spending.

- Consumers are still spending, but unevenly. Aggregate spending is holding up, supported by higher-income households who benefit most from rising asset values and One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) tax incentives. Beneath the surface, lower-income households face pressure from elevated debt service costs, housing affordability, and shadow debt obligations.

- AI is both a tailwind and a risk. Worldwide AI investment is projected to hit $1.5 trillion this year, dwarfing the scale of dot-com era private sector buildouts. While this has lifted profits and payrolls across industries, the sheer scale of investment brings risks of overcapacity and obsolescence. Still, the fear of missing out is fueling momentum and stock returns.

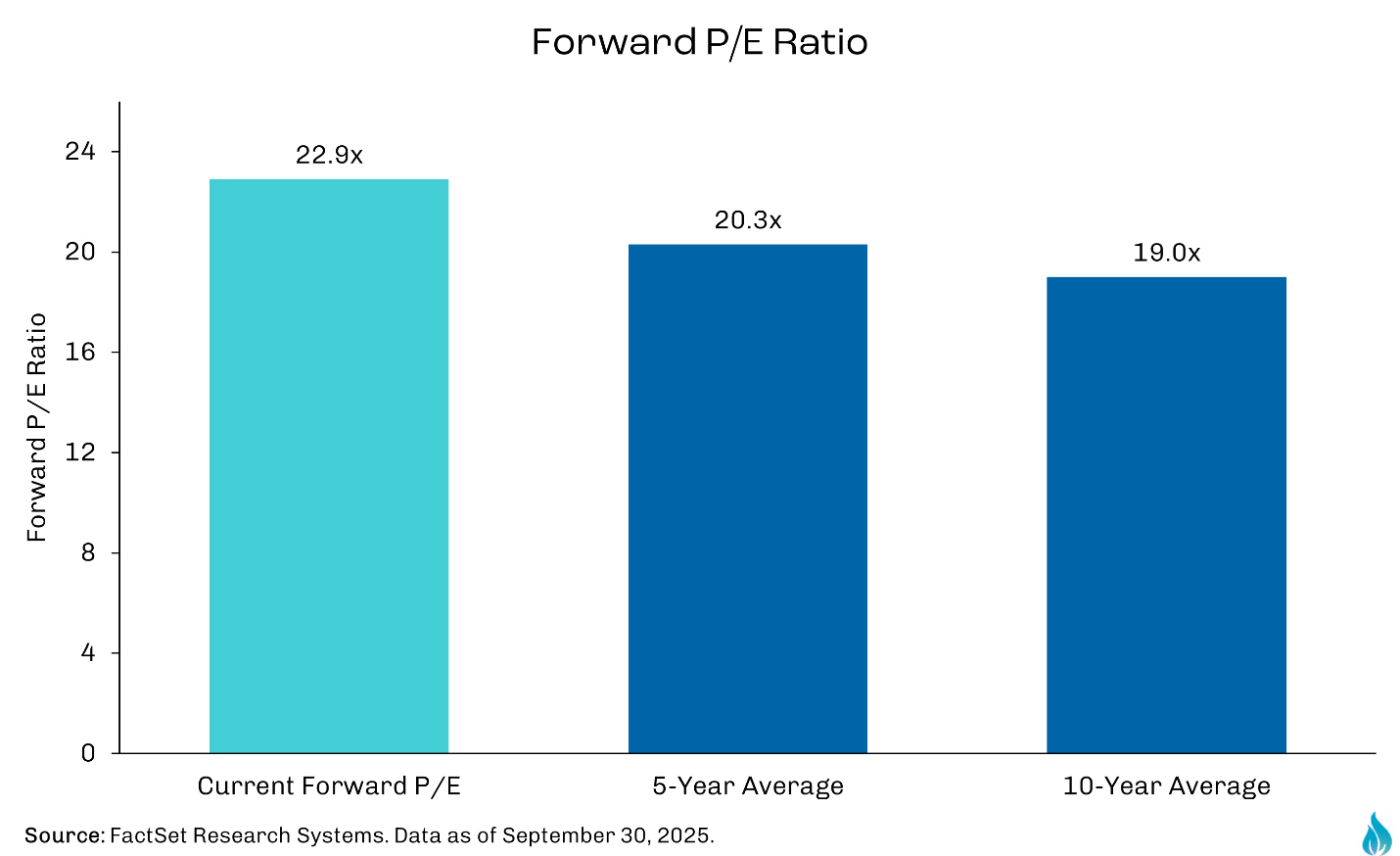

- Valuations leave little room for error. The S&P 500 trades at ~22.8x forward earnings, well above historical averages, while margins remain high at ~12.7%. History shows that sharp margin compression is a factor that drives layoffs and downturns. For now, earnings resilience and policy support are keeping valuations elevated, but the stakes are higher.

Introduction: Four Legs of the Stool

The continuation of the bull market rests on a four-legged stool: stimulus, the labor market, the U.S. consumer, and artificial intelligence (AI). While all four legs remain solid in varying degrees, as with any stool, small cracks can go unnoticed until the weight eventually becomes too much.

Stimulus is already at work, even if it doesn’t always feel that way. Upticks in mortgage refinancing and personal savings hint that government and Federal Reserve (Fed) measures are seeping into the economy. Like a double-shot espresso, fiscal and monetary policy can mask the fatigue of a late-cycle economy.

The labor market tells a more complicated story. Layoffs remain low, but hiring has slowed and participation has slipped. Foreign-born labor surged under the Biden administration and is now shrinking under Trump, while new H-1B rules raise questions about the future of high-skilled immigration.

The consumer continues to do the heavy lifting. Packed flights, busy restaurants, and record revenues at events like the Ryder Cup at Bethpage suggest little belt-tightening. My own wallet was lighter after the event, but I wasn’t alone. Consumers continue to spend on leisure and services, collectively fueling what remains the single largest engine of U.S. growth.

And then there’s the wild card that is AI. Investment in digital and energy infrastructure has spilled far beyond Silicon Valley, boosting profits and payrolls. The pace is staggering. Just last month, an open-source model reportedly passed the CFA Level III exam, a milestone that once took me six months of study. Like the early internet, AI inspires equal parts excitement and fear, two necessary ingredients often found in bubbles.

Together, these four legs continue to support the market and U.S. economy. As long as they stand, the expansion can endure and asset prices will continue to rise. But history also teaches us that if even one falters, the fall can be painful and abrupt.

Stimulus – A Heavy Dose

The combination of fiscal and monetary policy stimulus should not be overlooked. Historically, when fiscal expansion and easier monetary policy have coincided, the result has often been powerful tailwinds for both the economy and risk assets. In fact, since the 1970s, every major episode of synchronized stimulus, whether in response to recessions, crises, or even growth scares have supported financial assets. The backdrop today shares many of those characteristics.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) has already funneled more than $100 billion into R&D and capital investment this year, eclipsing the $94 billion collected from tariffs since March. According to Strategas, this has effectively offset the drag from trade frictions arising from uncertain policy. For higher-income households, who already account for a disproportionate share of consumption, the tax and investment incentives embedded in the legislation are meaningful and should sustain spending.

At the same time, Fed interest rate policy has pivoted toward a more dovish stance. After a long pause, the Fed delivered its first rate cut, and markets are now pricing in several more by year-end. The September FOMC “dot plot” revealed a majority of Fed officials now project at least 75–100 basis points (i.e., 0.75 – 1.00%) of additional cuts by mid-2026. At the press conference following the rate decision, Chair Powell emphasized that downside risks to employment have risen, giving the Fed room to act despite lingering inflation concerns.

In addition, a shift in the Fed’s balance sheet policy may alleviate pressure on longer term rates. Powell recently noted the Fed is “nearing ample reserves,” a signal that quantitative tightening, or QT, could soon end. If reinvestments shift from MBS runoff toward Treasuries, as Strategas points out, the effect would be to alleviate rate pressure further.

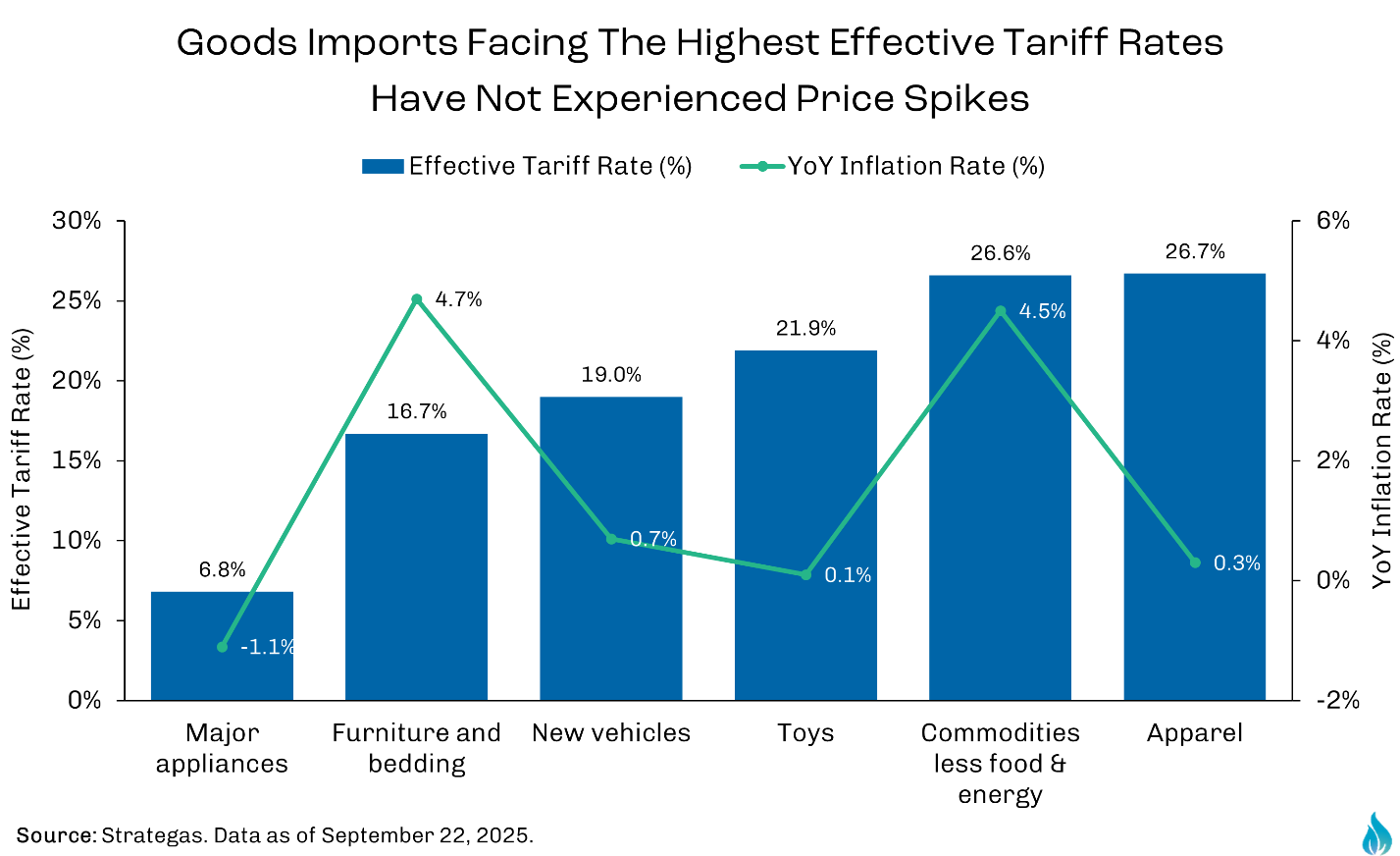

Of course, a shift in Fed policy is not a riskless proposition. Tariffs and supply chain pressures leave the inflation outlook highly uncertain. However, it is true that the effects of tariffs on inflation have been much more muted to date than forecasted by most economists.

In addition, political dynamics, most notably, the White House’s influence on Fed appointments, have raised legitimate concerns about the Fed’s independence. The appointment of Stephen Miran, aligned with Trump’s policy priorities, reinforces expectations of a pro-cut stance at the Fed, and the likelihood of Powell being replaced with a more dovish Fed Chair is high. While the long-term ramifications associated with the degradation of the Fed’s independence are unknown, in the short run, the likelihood of additional easing is heightened.

History suggests ignoring that combination of fiscal and monetary stimulus would be a mistake. They may not eliminate cracks forming in the economy, but they can patch them for longer, prolonging the cycle beyond its natural course.

Labor Market: Trends Indicate Late Stage?

The U.S. labor market has been under heavy scrutiny in recent months, and for good reason. Weakness in employment trends was one of the Fed’s justifications for its latest rate cut, even though inflation remains above target. While labor market data accuracy and integrity remain a challenge, the underlying trends suggest that while the labor market has weakened, it remains strong relative to history.

Unemployment is still low by long-term standards, and private-sector layoffs remain muted. Most of the recent job losses have been concentrated in the public sector, particularly government-related categories, while the private economy has largely maintained stability. According to UBS, the layoffs rate has inched up but is still well below historical averages, and steady initial claims remain consistent with an economy still in expansion.

With that said, cracks are forming. Hiring has slowed notably, a common characteristic of a late-cycle economy. Companies appear cautious, balancing the need to retain talent against growing uncertainty about tariffs, costs, and demand.

The labor force itself has also been shrinking. Participation rates have retreated toward historic lows, and the share of foreign-born workers has begun to fall again as immigration policy tightens. That has been particularly felt in industries like agriculture, hospitality, and construction, where immigrant labor is critical. Deportation policies have further reduced labor supply, complicating the picture for employers seeking to fill lower-wage roles.

As we have frequently communicated to our clients, the condition of the U.S. labor market continues to serve as a primary ballast. This is even truer today than it was 6 months ago. If the labor market turns meaningfully, pressure on the federal budget (e.g., higher unemployment claims and reduced tax revenue) and household balance sheets after years of elevated inflation could lead to a downward economic spiral. Elevated consumer debt from credit cards, auto loans, student debt, and “buy-now-pay-later” (BNPL) programs amplify the concern.

In short, the labor market is still healthy but increasingly late cycle. Job creation is slowing, layoffs remain low, and companies appear hesitant to either hire or fire. Stimulus can provide support temporarily, but it won’t eliminate the risks. With the consumer so dependent on stable employment, this is the leg of the stool we watch most closely.

The Consumer: Strong but Uneven

The U.S. consumer continues to power nearly 70% of the U.S. economy. Retail sales surprised to the upside this summer, and real consumption growth has accelerated modestly. Anecdotally, recent business travel points us toward a similar conclusion. Whether packed flights, crowded restaurants, or continued attendance at high priced experiential events, people are out spending with little indication of slowing down.

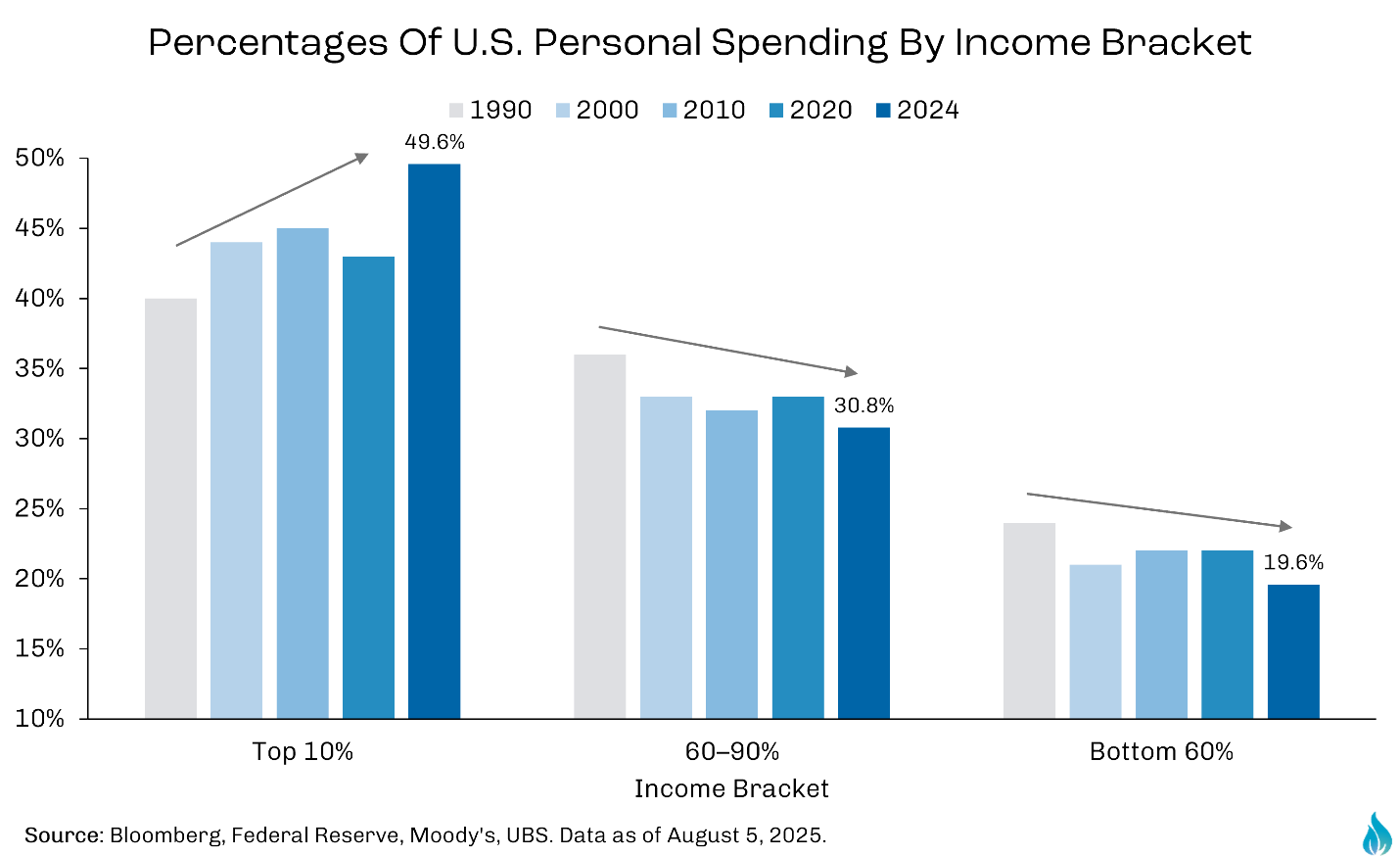

Beneath the surface, however, the picture is uneven. Consumer spending still looks strong largely because the top decile of earners, who benefit most from rising portfolio values and tax incentives embedded in the OBBBA, account for an outsized share of consumption. Meanwhile, younger and lower-income households are feeling the squeeze. Credit card delinquencies have leveled off but remain elevated at the 90-day mark, and subprime auto loan borrowers continue to show stress. Meanwhile, BNPL programs are spreading hidden leverage across households, often outside of traditional credit reporting. Even with wages up, debt service costs and higher living expenses are eroding purchasing power.

Strategas describes today’s consumer as a “K-shaped” economy: higher earners are reaping most of the post-pandemic gains, while lower earners struggle. This imbalance is masked in aggregate data but is critical to understanding risks. Housing illustrates these strains well. Mortgage rates have remained sticky, stalling the residential market and keeping affordability stretched. Refinancing activity has only just begun to recover as the Fed re-engages its cutting cycle. For most households, real estate has not yet returned as a driver of wealth creation and growth.

While some metrics show cracks in the consumer story, spending caution is understandable given the immense amount of negative news flow so far this year. We will be watching back-to-school and holiday spending closely. A disappointment in either could indicate deeper cracks beginning to form.

Artificial Intelligence: The FOMO is Real

The surge of investment in artificial intelligence has been one of the defining features of this cycle. Corporate spending on digital, computational, and energy infrastructure is now measured in trillions. Gartner projects worldwide AI spending will reach $1.5 trillion in 2025, encompassing hardware, software, services, and AI-enabled systems. That is likely 2x or more larger in scale than the dot-com era private buildouts. The margin grows even more when factoring in the broader scope (e.g., software, services) and the velocity of capital deployment.

This surge has lifted profits, payrolls, and valuations. Our clients have benefited from holdings in leading AI infrastructure and platform names. Yet the sheer scale of today’s AI investment also introduces fragility. Just as the dot-com boom featured massive overbuilds, today’s AI investments carry the risk of overcapacity, overspending, or disappointing returns if adoption or monetization lags expectations. And because the underlying technology and hardware are advancing rapidly, today’s capital-intensive buildout also risks becoming obsolete faster than expected, leaving investors and companies exposed if the payoff doesn’t keep pace.

Consider that in the late 1990s, few doubted the internet’s transformative power but many capital investments proved excessive when traffic and revenue didn’t materialize as fast as hoped. Today, AI is often framed as the most transformative leap since the internet, and the fear of missing out is widespread among CEOs, governments, and investors alike. That urgency is fueling capital expenditures (capex) and investment decisions that may outpace fundamentals.

Much of the early spending has centered on the enabling layer: GPUs, data centers, cloud infrastructure, power and cooling systems. But if Gartner’s projection holds, the next wave should emphasize intelligence and applications, where monetization can truly scale beyond just infrastructure. That transition is essential for sustaining AI’s long-term return narrative.

While profitability and cash flow are critical for the companies making the AI investments, the real economic payoff will hinge on how effectively AI boosts productivity across the broader economy. Early signals are promising. Goldman Sachs research shows that productivity in technology and professional services is already outpacing other sectors, a trend that may reflect the first tangible benefits of AI adoption.

In short, AI remains a powerful leg of the stool. But the leap from hundreds of billions to over a trillion in spending raises the stakes. History shows that bubbles rarely form and burst overnight. Instead, they tend to build over years. Fear of missing out often drives companies to spend beyond what’s necessary, but as long as that fear endures, capital will likely keep flowing, valuations can keep rising, and returns may remain strong. The urgency to stay ahead, even at the risk of overspending, is what can sustain current momentum.

Valuations and Earnings: Still Elevated

Valuations across U.S. equities are stretched. The S&P 500 trades at ~22.8x forward earnings, well above its 5-year average of ~19.9x and 10-year average of ~18.6x. Yet the forward multiple is rising faster than earnings themselves. In other words, markets are pricing in a lot of good news already, leaving little room for disappointment.

With that said, earnings resilience remains a positive. FactSet projects 8.0% year-over-year EPS growth in Q3, marking the ninth consecutive quarter of positive growth. Analysts have even revised estimates upward during the quarter, driven by strength in technology, semiconductors, and energy.

Margins are another important piece of the puzzle. At ~11.6% S&P 500 net margins remain historically elevated, giving companies breathing room to absorb higher costs. However, margin erosion is an important risk to be aware of given the relationship to corporate layoffs. History shows it’s not the level of margins that prompts layoffs, it’s the speed of decline. When aggregate margins compress by 150–200 basis points (i.e., 1.50 – 2.00%) within a year, job cuts typically accelerate. In 2000–2001, a ~200 basis point drop triggered mass layoffs in tech and telecom. In 2008, margins collapsed ~400 basis points from their peaks, unleashing widespread job losses. Today’s high margins offer cushion, but a sudden compression could quickly affect employment and spending.

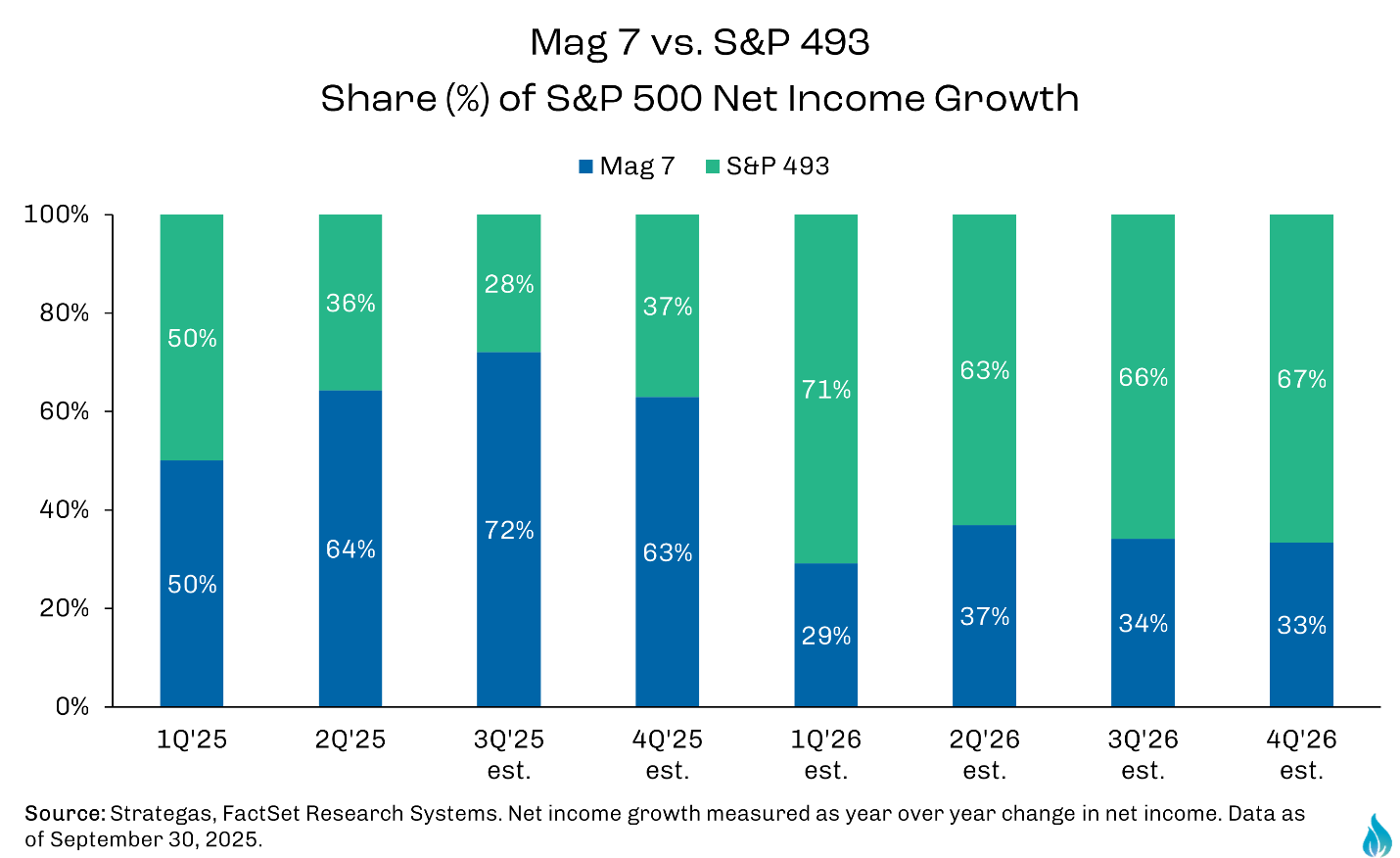

Much has been made of the concentration of large technology companies as a proportion of the stock market. With that said, the story continues and augments the importance of a continuation of the AI theme. The Magnificent 7 accounts for more than 60% of S&P earnings growth this year and nearly two-thirds of next year’s projections, with forward multiples stretching into the 20–30x range. Encouragingly, sectors like healthcare, financials, and industrials are beginning to contribute more meaningfully, suggesting some broadening beneath the surface. Interest rate cuts could support market breadth, but it’s more likely that the big continue to get bigger, reaping the rewards of scale and access to capital.

While we have remained overweight U.S. markets, international equities have been one of 2025’s bright spots, boosted by a weaker U.S. dollar. Relative valuations abroad are more compelling, though now toward the top of their 10-year ranges. Going forward continued dollar softness could be a tailwind for international stocks, but structural issues remain. As for fixed income, the opportunity set appears to be attractive. With rates likely moving lower, current bond coupons look appealing. Cash has been a great bond substitute in recent years, but those yields will fade as the Fed eases. We favor locking in intermediate investment-grade corporates and municipals as reliable income sources and as a potential hedge if growth slows.

While concern about valuations is valid, high valuations themselves rarely end expansions. Expensive markets can remain expensive when earnings and policy provide support. However, elevated multiples amplify downside risks as disappointments are punished more harshly. Conversely, if those legs of the stool hold, markets have the potential to grind higher.

Conclusion

The market and U.S. economy has remained resilient in 2025 despite policy uncertainty and high valuations. Our belief is that the combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus, a fully employed economy, continued consumer spending, and AI infrastructure buildout are the primary drivers of economic stability to be mindful of going forward. While each comes with potential risk, the cracks appear to be manageable for now.

As we approach year-end, our attention will turn to portfolio positioning and research with these four drivers firmly in mind. High valuations heighten the stakes, but they also mean that corrections can present opportunities if the underlying fundamentals remain intact. We will continue to look for selective entry points, both in equities and fixed income, and will also be mindful of opportunities to tax-loss harvest where appropriate. While the market cycle is maturing, it may yet still have some room to run.

The information in this report was prepared by Fire Capital Management. Any views, ideas or forecasts expressed in this report are solely the opinion of Fire Capital Management, unless specifically stated otherwise. The information, data, and statements of fact as of the date of this report are for general purposes only and are believed to be accurate from reliable sources, but no representation or guarantee is made as to their completeness or accuracy. Market conditions can change very quickly. Fire Capital Management reserves the right to alter opinions and/or forecasts as of the date of this report without notice.

All investments involve risk and possible loss of principal. There is no assurance that any intended results and/or hypothetical projections will be achieved or that any forecasts expressed will be realized. The information in this report does guarantee future performance of any security, product, or market. Fire Capital Management does not accept any liability for any loss arising from the use of information or opinions stated in this report.

The information in this report may not to be suitable or useful to all investors. Every individual has unique circumstances, risk tolerance, financial goals, investment objectives, and investment constraints. This report and its contents should not be used as the sole basis for any investment decision. Fire Capital Management is a boutique investment management company and operates as a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA). Additional information about the firm and its processes can be found in the company ADV or on the company website (firecapitalmanagement.com).

CFA® and Chartered Financial Analyst® are trademarks owned by CFA institute.

Michael J. Firestone, CFA

Michael is the founder of Fire Capital Management.

.png)